“For 50 Years, They Thought He Was a Wax Figure — Until a New Curator Discovered the Truth That Shook a Town”

The smell was the first thing that struck Clara Whitman — faint but wrong, like old varnish mixed with something she couldn’t name.

It came from the back room of the Pine Bluff Historical Museum, a small-town institution in rural Missouri where Clara had recently been hired as curator. The museum was the kind of place where time felt slower, where the floorboards creaked with stories no one had written down, and every artifact carried a ghost of the past.

That June morning in 2025, sunlight filtered through dusty windows as she walked through the exhibits, clipboard in hand. She was preparing for a renovation — new lighting, new labels, maybe even a digital guide. The board had hired her because she had a passion for giving forgotten history new life.

But nothing could have prepared her for what she was about to find.

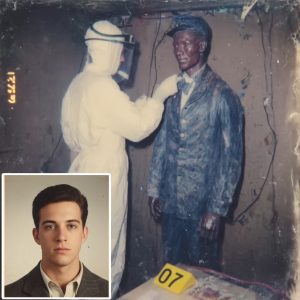

The Silent Man in the Corner

For fifty years, the museum’s prized “wax figure” — a man in a brown suit and bowler hat, seated with a newspaper in his lap — had been the centerpiece of the “Everyday Life in 1920” exhibit.

Children posed beside him during school trips. Tourists joked about how “real” he looked. The staff affectionately called him Sam the Silent Man.

He’d been sitting there longer than most of the staff had been alive.

But as Clara walked through the room, clipboard against her chest, that strange smell pulled her back.

She crouched beside the figure, inspecting his shoes, his hands, the way the light played across his cheek. Something was off. The texture of the skin wasn’t waxy — it was leathery.

Her fingers hovered above his hand. The fingernails had half-moon ridges — too natural. She felt a chill run through her arms.

Then, beneath a small tear near the collar, she saw it — a faint pattern, unmistakable even under the decades of dust.

Human skin.

She stepped back, heart hammering.

For several seconds, the museum was utterly still. The hum of the air conditioner. The ticking of a distant clock. And a man who wasn’t supposed to be real.

The Discovery

Clara forced herself to sound calm as she called maintenance. “I need this mannequin moved,” she said, her voice too bright. “Carefully.”

When the workers arrived and lifted him, a brittle crack echoed through the air. One man cursed and nearly dropped the figure.

“What was that?” he asked.

Clara swallowed. “Bone,” she whispered.

Within hours, the museum was sealed off with yellow tape. Police swarmed the scene, radios crackling, reporters hovering by the doors.

By evening, the verdict was in: the “wax figure” wasn’t wax at all. It was a mummified man, preserved by decades of dry air and shellac layered by well-meaning curators who had tried to keep their “exhibit” from cracking.

The news rippled through Pine Bluff like wildfire.

For half a century, the museum had displayed a missing person, sitting quietly under glass — and no one had known.

Detective Mercer Arrives

Detective Ryan Mercer arrived that same evening — mid-forties, calm, methodical, the kind of man who carried quiet authority.

He’d seen plenty in his career — drug busts, accidents, cold cases. But this? A corpse displayed as art for fifty years? It was something out of a gothic novel.

The autopsy confirmed the man had died around the early 1970s. No signs of violence, but no identification either.

Clara sat in her office late that night, staring at the exhibit through the glass doors. She couldn’t shake the feeling that the man — whoever he was — had been waiting.

The Carnival Connection

The next week, Mercer and Clara began combing through the museum’s archives. Most of the acquisition records were handwritten, yellowed, and half-faded.

Then Clara spotted a single note, scrawled in blue ink from 1974:

“Received donation from traveling carnival — Harlan’s Marvels.”

That name sent Mercer digging deeper.

Harlan’s Marvels had been a touring sideshow — the kind of carnival that roamed the Midwest in the 1960s and 70s, featuring oddities, fortune-tellers, and curiosities.

When Mercer tracked down old newspaper clippings, one headline stood out:

“Harlan’s Marvels Closes Amid Mystery of Owner’s Disappearance.”

The owner, Eddie Harlan, had vanished in 1974 — the same year the museum received its mysterious “wax figure.”

A Horrifying Realization

Former carnival workers were scattered across states, but Mercer managed to find one — Charlie Dunn, now 83 and living in Oklahoma.

“I remember that thing,” Charlie said over the phone, voice gravelly with age. “They called it The Time Traveler. Supposedly a real embalmed man — proof of time travel gone wrong. We all thought it was a gag.”

“Did anyone know where it came from?” Mercer asked.

“Eddie said he bought it from some mortuary auction, I think. Said it was a steal. But when the carnival folded, we sold everything off cheap. Guess your museum got it next.”

The Pine Bluff Museum, according to its ledger, had purchased “The Time Traveler” for $30.

Thirty dollars for a man’s body.

The Name Behind the Face

The body’s DNA was sent to a national database. Weeks passed. Reporters camped outside the museum gates. The story hit every major outlet:

“WAX FIGURE FOUND TO BE REAL HUMAN BODY AFTER 50 YEARS.”

“SMALL TOWN’S MUSEUM HID A MUMMY — AND NOBODY KNEW.”

Finally, the DNA results came back.

The man was Arthur L. Maier, a traveling salesman from Kansas City who had disappeared in 1973 on his route to Tulsa. His car had been found abandoned at a gas station, but his body had never been recovered.

His daughter, Susan Maier, was 64 now, living in Denver. When the police contacted her, she broke down on the phone.

“All these years,” she whispered, “I thought he left us. My mother died thinking he’d run away.”

When Clara showed her a photo of the museum’s “Sam the Silent Man,” Susan covered her mouth, tears spilling down her cheeks.

“That’s him,” she said softly. “That’s my dad.”

The Ethics of Forgetting

The coroner ruled Arthur’s death as likely natural — heart failure, perhaps heat stroke.

The tragedy wasn’t murder — it was neglect, misunderstanding, and the slow erosion of human dignity.

Arthur Maier had died alone, been mistaken for a prop, sold, displayed, and stared at by thousands.

When Clara spoke to a local journalist, she said quietly:

“It’s not the horror that gets me. It’s the indifference. That he sat there for fifty years, and no one saw him.”

A Burial, At Last

By August, Arthur’s remains were released to his family. The funeral took place in Kansas City under a clear blue sky.Family vacation packages

His daughter Susan stood beside the small headstone that read:

“Arthur L. Maier — Finally Home.”

Clara attended too, standing quietly in the back.

She’d only meant to restore an exhibit, but she’d uncovered a tragedy — a man erased by time, rediscovered by accident.

After the service, Susan hugged her.

“My father can rest now,” she said. “Because you cared enough to look closer.”

The Man We Didn’t See

When the museum reopened six months later, the “Everyday Life in 1920” exhibit looked different.

Where the wax figure once sat, there was a new display titled “The Man We Didn’t See.”

Behind glass sat Arthur’s belongings: a replica of his newspaper, a bowler hat, and the faded photo of him smiling beside his 1972 sedan.

The plaque read:

“For fifty years, this man was known only as Sam the Silent Man.

His name was Arthur L. Maier.

May we never forget the stories hidden in plain sight.”

Visitors came from across the country. Some left flowers. Others wrote messages in the guestbook:

“Rest in peace, Arthur.”

“You were finally seen.”

The Story That Echoed

The media frenzy faded, but the story lingered.

Universities used the case in museum ethics courses. The Smithsonian published an article titled “When History Forgets It’s Human.”

Documentaries followed. Clara appeared in one, speaking softly about the lessons she’d learned.

“Museums are about memory,” she said. “But sometimes, we forget that the objects we preserve once belonged to living people. In this case, one of them still was.”

What Came After

Months passed, and Clara’s life changed.

She was invited to lecture across the country on artifact provenance, the process of tracing an item’s origin. She worked with other small museums to ensure no history — or person — would ever be misidentified again.

Detective Mercer remained in touch, often visiting the exhibit on quiet mornings. “You didn’t just find a body,” he told her one day. “You found a lesson.”

Clara smiled faintly. “No,” she said. “He found us.”

A Town That Remembered

By the following year, attendance at the Pine Bluff Museum had tripled. But more important than numbers was the tone. The laughter that once filled the hall had softened into reverence.

Visitors didn’t just come to see anymore — they came to remember.

And every morning, before opening hours, Clara walked through the quiet building, past the glass case.

The sunlight would strike the photo of Arthur Maier, catching the warmth of his easy smile.

For a moment, it felt like he was finally seen — not as a curiosity, not as an exhibit, but as a man who had lived, loved, and was, at last, remembered.

Months later, Clara flipped through the museum’s guestbook. Hundreds of signatures, thousands of messages.

But one page stopped her. A neat cursive note read:

Clara closed the book gently.Bookshelves

Outside, the Missouri sky glowed orange with sunset.

History, she thought, isn’t just what we preserve. It’s what we finally see.

And in Pine Bluff, they had finally seen the man who had sat in silence for fifty years — not a wax figure, not a curiosity, but a human being waiting to be remembered.