In 1912, three young ladies posed for a picture in front of a mill without giving it any thought. However, when scientists delved deeper a century later, they discovered a startling fact that astounded them. Cotton lint floated in the air of the ill-ventilated room as the Porte Mill pulsed with the thunderous clatter of machinery.

Pearl Turner straightened her back and repositioned her clothing. They had been invited to go outdoors for a little moment by the photographer.

Viola, her older sister, smoothed down her own plain clothes and urged Pearly to hurry up.

We cannot leave our posts for longer than a few minutes, according to Mr. Himmel. As they entered the uncommon fresh air, Pearl said, “I’m coming,” while attempting to keep from coughing.

Pearl had already worked in the mill for three years at the age of nine, though she would turn ten in a few months. Her tiny fingers rapidly picked up the risky skill needed to run the spinning machine.

The females were placed in front of the mill’s accounting office by Thomas Himmel, the man with the camera. With a solemn yet dignified attitude, Pearl stood to the left, her black eyes displaying a maturity well beyond her years. Standing on the right was 14-year-old Viola, who was already displaying indications of exhaustion that seemed to emanate from her very bones.

Penelope, a 12-year-old neighbor girl who worked on the same level, was in between them. “Now stand motionless,” Mr. Himmel said, vanishing behind the black cloth covering his camera. There was a flash a moment later, and the girls’ pictures were permanently taken.

Three stiff, young faces are placed in front of the eerie workplace where they spent their formative years. None of them could have predicted that this one image would last for over a century and then reappear in the world to show something startling from a scientific standpoint.

After giving the man with the camera one final look, Pearl followed her sister back into the mill, which was a place of constant noise and floating lint that would soon have mind-numbing effects.

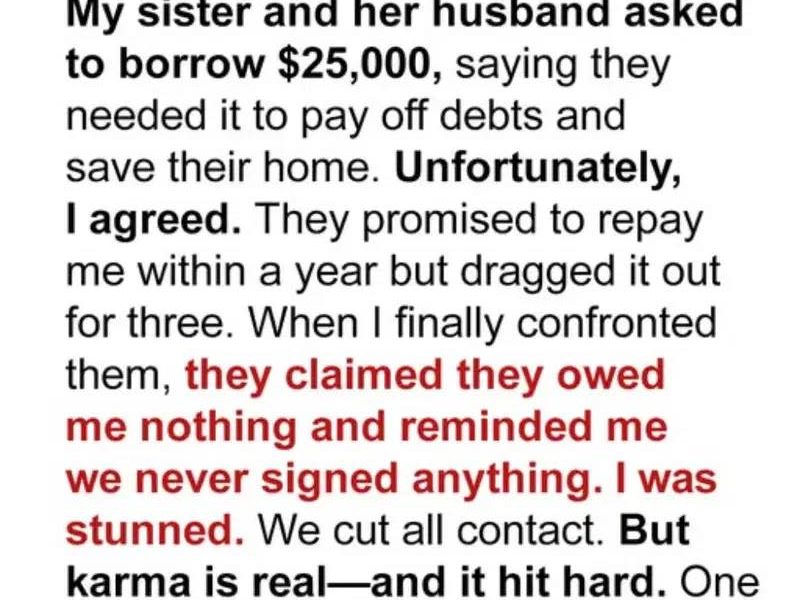

When Professor Sonia Abernathy looked up from her computer more than a century later, she saw Marcus, her research assistant, standing in her doorway, holding a manila folder and wearing an excited expression. What did you discover? She took off her reading glasses and asked. Reaching her desk, Marcus unfolded the folder.

We have been digitizing the Thomas Himmel collection. This image is from Three Mill Girls in Gastonia, taken in 1912. Sonia looked at the picture of three young girls standing in front of what looked like some kind of office, their faces stiff.

How about it? Hundreds of Himmel’s images of child labor have been shown to us. Take a look at this one. Marcus gestured toward the left-hand girl.

Himmel’s notes indicate that this is Pearl Turner, who has been employed at the mill for three years and is not quite ten years old. However, that isn’t the noteworthy aspect. He turned to another page.

I came across her obituary. She survived until 1964. For mill workers of that era, especially those who began so early, that is exceptional.

There’s more. Interviews with her children from 2006 and 2007 are on file. Sonia bent over.

She became quite interested. She organized historical facts for research and recreation, working as a professor by day and as an archivist in her spare time. She recently traveled back in time to a period when child labor was more common.

Despite the fact that the subject was often sad, she bottled up her feelings and confronted them. Her research helper Marcus was very enthusiastic and very different from her. He never really demanded in-depth research until it was absolutely necessary, but he always thought the small nuances were important.

It appeared that this new case was at least somewhat significant to him. Is it possible to obtain additional information from the archival image using facial recognition software? “I’m almost excited, or too excited now,” Marcus begged. It would be very beneficial to our research if we could improve this image.

I have written the letter of request. I just need your consent. After giving his request some more thought, Sonia nodded curtly in response.

Marcus was in a rare yet fascinating state of unique excitement. It made her hopeful for a breakthrough finding, for whatever reason. She had no idea how accurate this would turn out to be during their investigation.

Sonia gazed at her computer screen for three weeks, contrasting the improved image with other photographs and articles from the Thomas Himmel collection.

She expanded her search to other fields, such as weaving archives and medical publications, but nothing significant emerged. The majority of the work has been completed by Marcus, who has tracked down and interviewed everyone involved in the odd image.

Since Penelope was the only one of the three girls without a backstory, the initial goal was to analyze the picture and identify her. But when they researched more, Pearl became their primary focus instead of Penelope. the youngest person in the picture.

The two had a strange suspicion about her and her story for some reason. Sonia used scrutinizing slits to zoom in on Pearl’s photo, capturing every aspect of her personality.

Using the medical journals strewn over her desk, she matched every detail as she studied her face, skin tone, hair, and posture in the sepia lighting.

She tried for two days before making a breakthrough. Something that had been overlooked for more than a century was discovered in the original shot thanks to the university’s sophisticated digital imaging equipment. As she considered the ramifications of what they had discovered, her heart began to accelerate.

She reached for her phone to contact Marcus and murmured, “This changes everything we thought we knew about the health outcomes of textile mill workers.”

Go to the medical history department and get me Dr. Harold. Sonia found herself speaking in front of a group of historians and professors that evening, many of whom were from the medical history department.

The Thomas Himmel shot from 1912, digitally improved to reveal features not visible to the human eye, was projected on a huge screen behind her. “Hello everybody,” she said. Perhaps one of the decade’s most important historical medical discoveries is what you’re looking at.

Photographed in 1912 outside the Porte Mill in Gastonia, North Carolina, were three young girls. They labored long hours in hazardous conditions, like hundreds of children in that era, and were continuously exposed to lint and cotton fibers, which usually resulted in respiratory illnesses and early death. She selected the following slide, which displayed a close-up of Pearl Turner’s face.